B&W/Color, 1949-1980, 216 mins

BFI (Blu-ray) (UK RB HD)

B&W/Color, 1949-1980, 216 mins

BFI (Blu-ray) (UK RB HD)

as the short story has always been a potent vehicle for horror writers to chill their readers with innovative scare

as the short story has always been a potent vehicle for horror writers to chill their readers with innovative scare  tactics, the short film has been a way to play around with the genre ever since the silent era. Unfortunately that format has been largely neglected over the years apart from a few famous examples, with TV episodes taking over in the public consciousness when it comes to short-form horror filmmaking. Balancing out that oversight a bit is a two-disc Blu-ray release from the BFI, Short Sharp Shocks (taking its title from multiple screening programs they've held in the past) which compiles three decades' worth of highlights from the vaults in the finest existing quality to present a broad spectrum of how unnerving stories can be presented and sometimes stretch the definition of what constitutes horror far beyond what you'd normally expect. All of these, which were intended to support first-run feature films in the U.K. at the time, are interesting and welcome contributions to be sure, with one bona fide masterpiece in the set justifying the price tag all by itself.

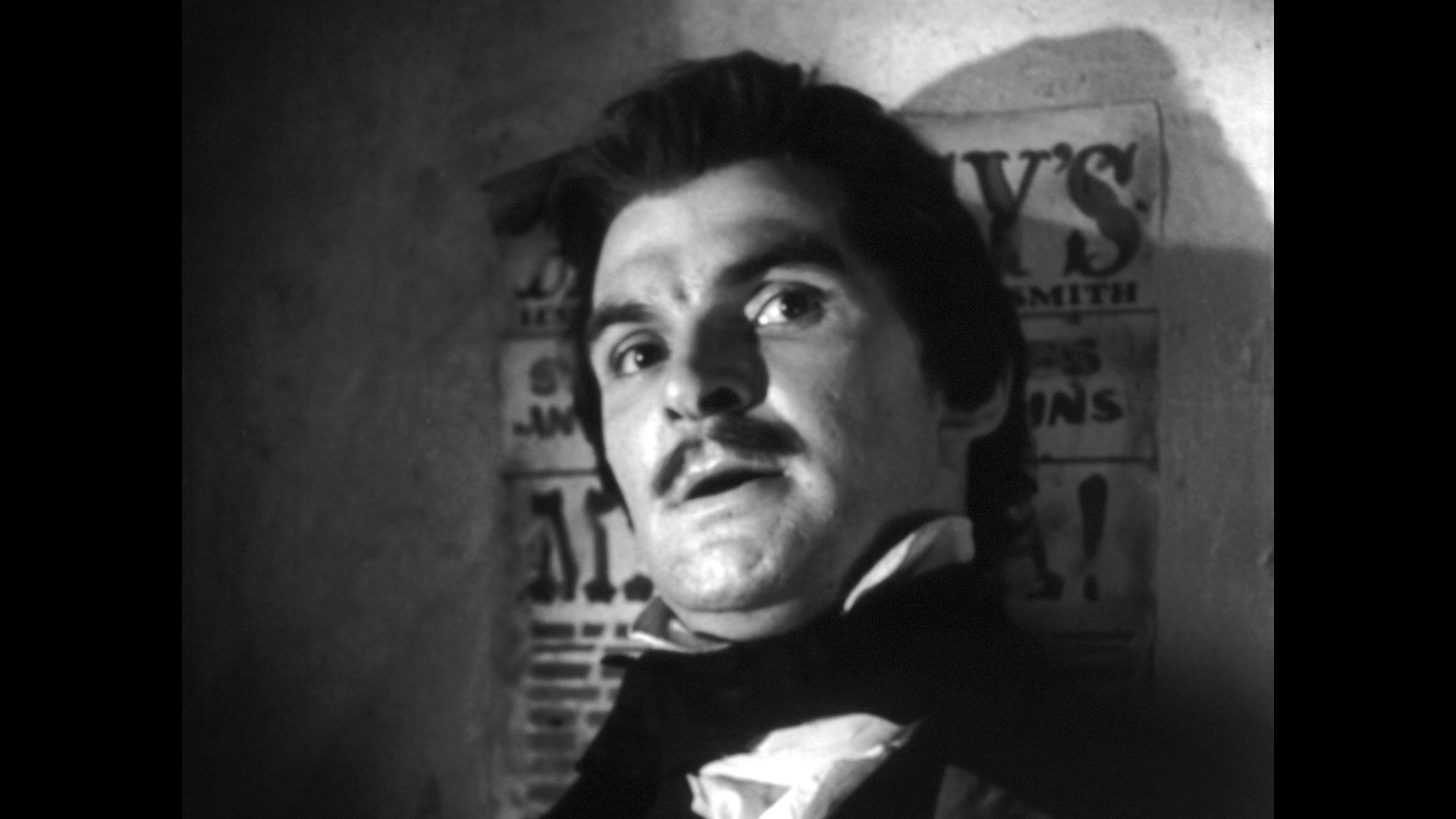

tactics, the short film has been a way to play around with the genre ever since the silent era. Unfortunately that format has been largely neglected over the years apart from a few famous examples, with TV episodes taking over in the public consciousness when it comes to short-form horror filmmaking. Balancing out that oversight a bit is a two-disc Blu-ray release from the BFI, Short Sharp Shocks (taking its title from multiple screening programs they've held in the past) which compiles three decades' worth of highlights from the vaults in the finest existing quality to present a broad spectrum of how unnerving stories can be presented and sometimes stretch the definition of what constitutes horror far beyond what you'd normally expect. All of these, which were intended to support first-run feature films in the U.K. at the time, are interesting and welcome contributions to be sure, with one bona fide masterpiece in the set justifying the price tag all by itself.  incident hinting at forces in the great beyond. Both take place entirely with the author relating the tales in an offhanded, relaxed style ambling around a firelit sitting room, always shot at slightly uncomfortable angles that break away from the standard blocking you normally see with his gaze seemingly fixed on someone elsewhere in the room. It's a peculiar technique that ends up imbuing both stories with a spooky air while offering a chance to see one of the unsung maestros of the form at work long before it would become common practice for other writers and directors in the TV age. On a similar note, 1953's once-lost The Tell-Tale Heart by J.B. Williams (20m39s) for the independent company Adelphi Films features none other than Stanley Baker (Zulu, A Lizard in a Woman's Skin) having a field day as Edgar Allan Poe, relating one of his most famous tales by the light of a flickering candle and building up to an appropriate fever pitch for the legendary floor-ripping finale.

incident hinting at forces in the great beyond. Both take place entirely with the author relating the tales in an offhanded, relaxed style ambling around a firelit sitting room, always shot at slightly uncomfortable angles that break away from the standard blocking you normally see with his gaze seemingly fixed on someone elsewhere in the room. It's a peculiar technique that ends up imbuing both stories with a spooky air while offering a chance to see one of the unsung maestros of the form at work long before it would become common practice for other writers and directors in the TV age. On a similar note, 1953's once-lost The Tell-Tale Heart by J.B. Williams (20m39s) for the independent company Adelphi Films features none other than Stanley Baker (Zulu, A Lizard in a Woman's Skin) having a field day as Edgar Allan Poe, relating one of his most famous tales by the light of a flickering candle and building up to an appropriate fever pitch for the legendary floor-ripping finale.  of the darker Ealing titles from the same decade. Then in the same year's Portrait of a Matador (24m26s), a somewhat goofy Alfred Hitchcock Presents-style oddity in which an artist

of the darker Ealing titles from the same decade. Then in the same year's Portrait of a Matador (24m26s), a somewhat goofy Alfred Hitchcock Presents-style oddity in which an artist  named David (Anthony Tancred) finds his artistic pursuits in Spain waylaid by his compulsive fixation on a painting of a bullfighter that's part of a larger and more nefarious, possibly supernatural scheme. You won't buy the explanation for a second, but it's an amusing slice of Spanish exotica pulled off on a British soundstage with atmosphere to burn. The first two shorts are presented in good quality from the fine-grain prints held in the BFI National Archive, while The Tell-Tale Heart is culled from the sole existing 16mm print and obviously looks dupier but is a very welcome addition. The two Zichy films are 2K transfers from the 35mm negatives and look spectacular here with an impressive amount of detail, no visible damage, and perfect black levels. All of the shorts feature LPCM English mono tracks (all good but obviously variable based on the existing elements) with optional English SDH subtitles. Extras on disc one include "Arthur Dent and Adelphi: Films in the Family" (29m11s) with the company's Kate Lees offering an in-depth and highly informative look at the family history of Adelphi Films, "Telling Tales" (7m41s) with Lees positively appraising the short and explaining how it was salvaged after years of oblivion, and an image gallery for The Tell-Tale Heart (3m30s).

named David (Anthony Tancred) finds his artistic pursuits in Spain waylaid by his compulsive fixation on a painting of a bullfighter that's part of a larger and more nefarious, possibly supernatural scheme. You won't buy the explanation for a second, but it's an amusing slice of Spanish exotica pulled off on a British soundstage with atmosphere to burn. The first two shorts are presented in good quality from the fine-grain prints held in the BFI National Archive, while The Tell-Tale Heart is culled from the sole existing 16mm print and obviously looks dupier but is a very welcome addition. The two Zichy films are 2K transfers from the 35mm negatives and look spectacular here with an impressive amount of detail, no visible damage, and perfect black levels. All of the shorts feature LPCM English mono tracks (all good but obviously variable based on the existing elements) with optional English SDH subtitles. Extras on disc one include "Arthur Dent and Adelphi: Films in the Family" (29m11s) with the company's Kate Lees offering an in-depth and highly informative look at the family history of Adelphi Films, "Telling Tales" (7m41s) with Lees positively appraising the short and explaining how it was salvaged after years of oblivion, and an image gallery for The Tell-Tale Heart (3m30s). from the tacky to the terrifying. In 1969's Twenty-Nine (26m27s) directed by Brian Cummins, is a swinging

from the tacky to the terrifying. In 1969's Twenty-Nine (26m27s) directed by Brian Cummins, is a swinging  variation on the amnesiac thriller formula (complete with a musical cameo by pop band Tuesday's Children) with a young bar-hopping man named Graham (Alexis Kanner, who made an indelible impression on The Prisoner and also appeared in Goodbye Gemini) trying to navigate the world of football and youth culture as he pieces together how he ended up in an unfamiliar apartment wearing someone else's clothes. As a thriller this is very low key and obviously inspired by the likes of Blow-up, but as a pop culture artifact it's really priceless with Kanner holding it all together as he wanders through a string of increasingly dark encounters. Then in the longest and sleaziest short in the set, 1973's The Sex Victims (37m1s) by Derek Robbins, we open with the sound of a woman screaming in the woods, after which a man quickly retreats from what seems to be the scene of a crime. From there we follow piggy truck driver Jack (From Beyond the Grave's Ben Howard) as he fixates on a nude woman seen riding on horseback through the woods as he traverses the countryside encountering other oddball characters, eventually settling into an afternoon sexual encounter that's far more than it appears to be. The rough and tumble nature of '70s exploitation filmmaking can be felt all throughout this one with its surreal female nudity and nutty plot twists, which go into really weird Twilight Zone territory at the end with an ironic finale. In short, this one's almost singlehandedly responsible for that "18" rating on the box.

variation on the amnesiac thriller formula (complete with a musical cameo by pop band Tuesday's Children) with a young bar-hopping man named Graham (Alexis Kanner, who made an indelible impression on The Prisoner and also appeared in Goodbye Gemini) trying to navigate the world of football and youth culture as he pieces together how he ended up in an unfamiliar apartment wearing someone else's clothes. As a thriller this is very low key and obviously inspired by the likes of Blow-up, but as a pop culture artifact it's really priceless with Kanner holding it all together as he wanders through a string of increasingly dark encounters. Then in the longest and sleaziest short in the set, 1973's The Sex Victims (37m1s) by Derek Robbins, we open with the sound of a woman screaming in the woods, after which a man quickly retreats from what seems to be the scene of a crime. From there we follow piggy truck driver Jack (From Beyond the Grave's Ben Howard) as he fixates on a nude woman seen riding on horseback through the woods as he traverses the countryside encountering other oddball characters, eventually settling into an afternoon sexual encounter that's far more than it appears to be. The rough and tumble nature of '70s exploitation filmmaking can be felt all throughout this one with its surreal female nudity and nutty plot twists, which go into really weird Twilight Zone territory at the end with an ironic finale. In short, this one's almost singlehandedly responsible for that "18" rating on the box. we reach the absolute highlight of the set, 1978's blood-freezing The Lake (33m7s) from Hammer Films veteran Lindsey C. Vickers. En route to an afternoon picnic at an isolated lake,

we reach the absolute highlight of the set, 1978's blood-freezing The Lake (33m7s) from Hammer Films veteran Lindsey C. Vickers. En route to an afternoon picnic at an isolated lake,  Barbara (Julie Peasgood) and Tony (Gene Foad) along with their dog, Condor, stop off at an abandoned house that had been the site of a brutal mass murder three years earlier in which a man had slaughtered his wife, their two children, and all of the animals on the property. After exploring the area, they head on to the lake (which is still part of the same property) where something seems to be following them... but that's just the start of their ordeal. A prime example of chilling daylight horror, The Lake uses brilliant sound design and an escalating sense of dread to build to an unforgettable finale; you could easily use this as an appetizer for either Let's Scare Jessica to Death or Creepshow 2 in the "scary lake" sweepstakes. Finally 1980's The Errand (28m41s), directed by Nigel Finch and written by David McGillivray (Frightmare, Terror), begins at a remote pastoral military base where a young captain (J. Edward Kalinski) is sent on an errand, or perhaps "more than just an errand," across the region where he's set upon by a pair of attempted assassins who leave him scrambling for help. Borderline abstract for much of its running time, this entry features one perfectly timed jump scare and an effective, Tales of the Unexpected-style twist ending that works even if you've

Barbara (Julie Peasgood) and Tony (Gene Foad) along with their dog, Condor, stop off at an abandoned house that had been the site of a brutal mass murder three years earlier in which a man had slaughtered his wife, their two children, and all of the animals on the property. After exploring the area, they head on to the lake (which is still part of the same property) where something seems to be following them... but that's just the start of their ordeal. A prime example of chilling daylight horror, The Lake uses brilliant sound design and an escalating sense of dread to build to an unforgettable finale; you could easily use this as an appetizer for either Let's Scare Jessica to Death or Creepshow 2 in the "scary lake" sweepstakes. Finally 1980's The Errand (28m41s), directed by Nigel Finch and written by David McGillivray (Frightmare, Terror), begins at a remote pastoral military base where a young captain (J. Edward Kalinski) is sent on an errand, or perhaps "more than just an errand," across the region where he's set upon by a pair of attempted assassins who leave him scrambling for help. Borderline abstract for much of its running time, this entry features one perfectly timed jump scare and an effective, Tales of the Unexpected-style twist ending that works even if you've  anticipated something like it by the midway point; the weird air of paranoia is also nicely handled and, as with the prior title, uses the English countryside to appropriately eerie effect. This disc features a much heftier slate of extras starting with "Man With a Movie Camera" (41m47s), a very colorful new interview with Twenty-Nine producer Peter Shillingford about his wild life in the entertainment business and elsewhere rubbing shoulders with some very famous figures. Then in "A Crazy, Mixed-up Kid" (42m47s), the always entertaining McGillivray chats about his early life, the challenges of being gay in a more restrictive time, his entry into filmmaking, and his love of genre cinema as well as his evolution to taking on more responsibilities beyond writing including producing and making his own recent shorts. In "Almost Thirty" (15m12s), Renée Glynne, script supervisor on Twenty-Nine, recalls her own career including the state of British filmmaking at the time, the process of handling continuity on productions like this one, and the joys of being flashed by Mick Jagger. Finally, "Splashing Around" (17m52s) features Peasgood talking about much more than The Lake as she covers her entire career including a stint in House of the Long Shadows. Seven galleries are also included: "Life Behind the Lens" (3m50s) featuring some eye-popping highlights from Shillingford's career; the production of The Lake (1m50s) and The Errand (2m20s); the shooting and annotated scripts for The Lake; and the shooting script and original short story for The Errand. Limited to 3,000 copies, the set also features cover art by Graham Humphreys and a hefty insert booklet featuring liner notes by Vic Pratt, Josephine Botting, William Fowler, Jonathan Rigby, Shillingford, Vickers and a hilariously candid McGillivray.

anticipated something like it by the midway point; the weird air of paranoia is also nicely handled and, as with the prior title, uses the English countryside to appropriately eerie effect. This disc features a much heftier slate of extras starting with "Man With a Movie Camera" (41m47s), a very colorful new interview with Twenty-Nine producer Peter Shillingford about his wild life in the entertainment business and elsewhere rubbing shoulders with some very famous figures. Then in "A Crazy, Mixed-up Kid" (42m47s), the always entertaining McGillivray chats about his early life, the challenges of being gay in a more restrictive time, his entry into filmmaking, and his love of genre cinema as well as his evolution to taking on more responsibilities beyond writing including producing and making his own recent shorts. In "Almost Thirty" (15m12s), Renée Glynne, script supervisor on Twenty-Nine, recalls her own career including the state of British filmmaking at the time, the process of handling continuity on productions like this one, and the joys of being flashed by Mick Jagger. Finally, "Splashing Around" (17m52s) features Peasgood talking about much more than The Lake as she covers her entire career including a stint in House of the Long Shadows. Seven galleries are also included: "Life Behind the Lens" (3m50s) featuring some eye-popping highlights from Shillingford's career; the production of The Lake (1m50s) and The Errand (2m20s); the shooting and annotated scripts for The Lake; and the shooting script and original short story for The Errand. Limited to 3,000 copies, the set also features cover art by Graham Humphreys and a hefty insert booklet featuring liner notes by Vic Pratt, Josephine Botting, William Fowler, Jonathan Rigby, Shillingford, Vickers and a hilariously candid McGillivray.![]()