KEN RUSSELL: THE GREAT COMPOSERS

ELGAR

B&W,

1962, 50m.

Starring Huw Wheldon, Peter Brett, Rowena Gregory, George McGrath

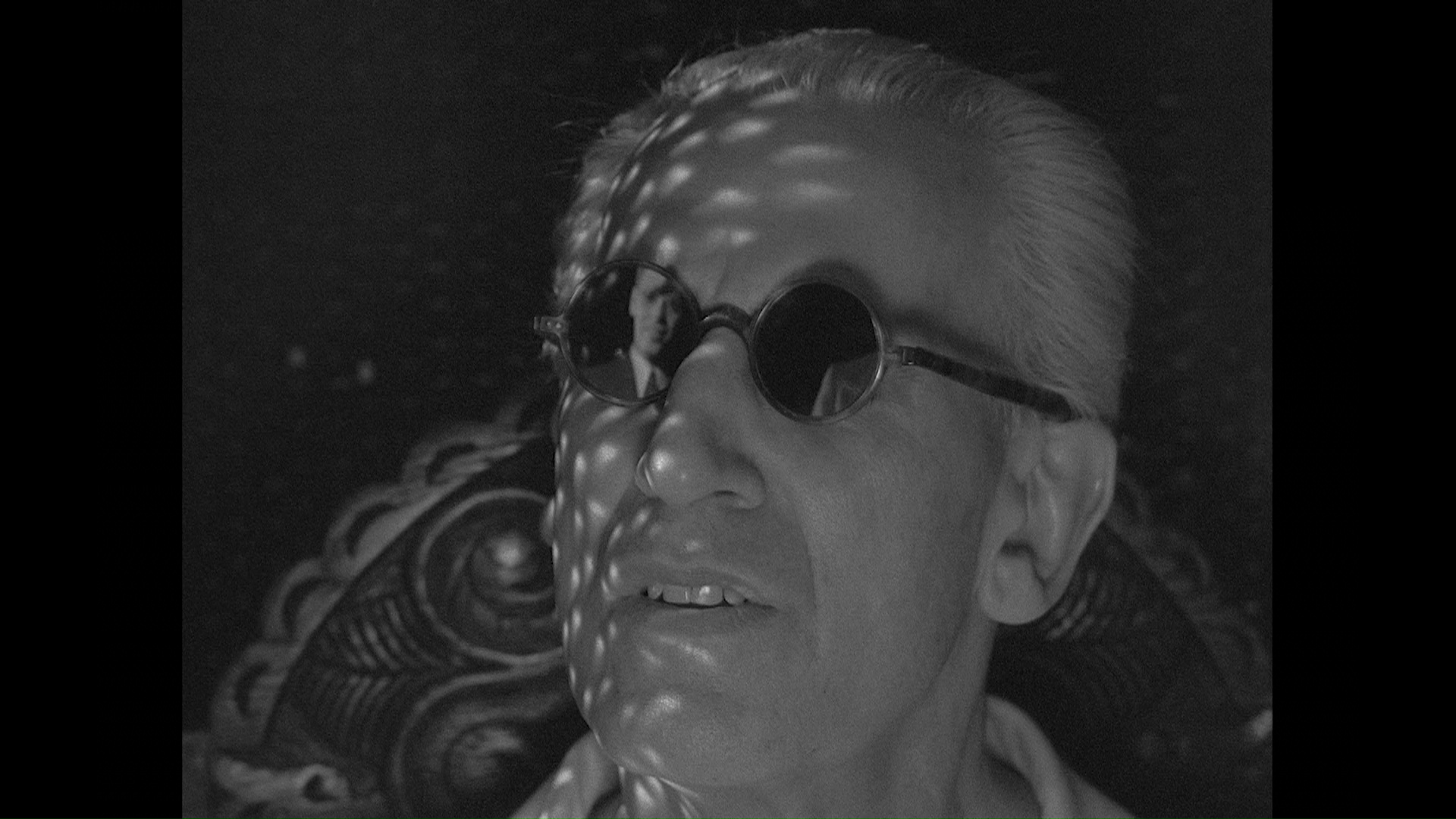

THE DEBUSSY FILM

B&W, 1965, 82m.

Starring Oliver Reed, Vladek Sheybal, Annette Robertson

SONG OF SUMMER

B&W, 1968, 73m.

Starring Max Adrian, Maureen Pryor, Christopher Gable, David Collings

KEN RUSSELL: THE GREAT PASSIONS

ALWAYS ON SUNDAY

B&W, 1965, 45m.

Starring

James Lloyd, Annette Robertson, Bryan Pringle ISADORA DUNCAN, THE BIGGEST DANCER IN THE WORLD

B&W, 1966, 65m.

Starring

Vivian Pickles, Peter Bowles, Alexei Jawdokimov, Murray MelvinDANTE'S INFERNO

B&W, 1967, 87m.

Starring

Oliver Reed, Judith Paris, Andrew Faulds

BFI (Blu-ray & DVD) (UK RB/R2 HD/PAL), BBC Home Entertainment (DVD) (US R1 NTSC)

Before he hit the feature film big time with a psychedelic spy film and the groundbreaking Women in Love, director Ken Russell had already honed his energetic, sometimes feverish approach to filmmaking (and artistic biopics in particular) with a string of short films and TV productions, the latter producing several titles still regarded as some of his best work. Six key titles from his BBC days have tended to pop up together (with one notable holdout, 1970's Dance of the Seven Veils for the program Omnibus, still a holdout due to legal reasons), with their home video history encompassing some separate DVD debuts from the BFI early in the format's history, a collected (but flawed) set in the United States from the BBC itself, and best of all, two collections as dual-format Blu-ray and DVD editions from the BFI.

Before he hit the feature film big time with a psychedelic spy film and the groundbreaking Women in Love, director Ken Russell had already honed his energetic, sometimes feverish approach to filmmaking (and artistic biopics in particular) with a string of short films and TV productions, the latter producing several titles still regarded as some of his best work. Six key titles from his BBC days have tended to pop up together (with one notable holdout, 1970's Dance of the Seven Veils for the program Omnibus, still a holdout due to legal reasons), with their home video history encompassing some separate DVD debuts from the BFI early in the format's history, a collected (but flawed) set in the United States from the BBC itself, and best of all, two collections as dual-format Blu-ray and DVD editions from the BFI. riding as a boy through depression and illness, the film captures his lifelong

riding as a boy through depression and illness, the film captures his lifelong  love affair with music (which led to him being branded a symbol of the outdated establishment) and builds to a very memorable finale few viewers have ever forgotten. The nonstop narration (peppered with quotes from actual diary entries and letters) somehow doesn't feel like a dry history lesson, instead mingling well with the waves of music and powerful images.

love affair with music (which led to him being branded a symbol of the outdated establishment) and builds to a very memorable finale few viewers have ever forgotten. The nonstop narration (peppered with quotes from actual diary entries and letters) somehow doesn't feel like a dry history lesson, instead mingling well with the waves of music and powerful images.  (whose 8 1/2 was still fresh in the public consciousness and gets quoted overtly here). It's also fascinating as a precursor of sorts to The Boy Friend, in which Russell found a similar solution to adapting a simple stage musical hit for the big screen.

(whose 8 1/2 was still fresh in the public consciousness and gets quoted overtly here). It's also fascinating as a precursor of sorts to The Boy Friend, in which Russell found a similar solution to adapting a simple stage musical hit for the big screen.  the final years in the life of composer Frederick Delius. Hearing that blindness and paralysis have rendered Delius (Adrian) unable to preserve the melodies still surging in his head, a young composer and organist named Eric Fenby (Gable), who in real life went on to score Alfred Hitchcock's Jamaica Inn, to offer his services for five years to take down and play the music dictated by Delius. The process starts off turbulently, but with the aid of Delius's wife, Jelka (Pryor), the process of transcribing the compositions to paper begins to take shape in between readings from the novels of Mark Twain.

the final years in the life of composer Frederick Delius. Hearing that blindness and paralysis have rendered Delius (Adrian) unable to preserve the melodies still surging in his head, a young composer and organist named Eric Fenby (Gable), who in real life went on to score Alfred Hitchcock's Jamaica Inn, to offer his services for five years to take down and play the music dictated by Delius. The process starts off turbulently, but with the aid of Delius's wife, Jelka (Pryor), the process of transcribing the compositions to paper begins to take shape in between readings from the novels of Mark Twain.  DVD of Song of Summer, a fascinating study in how he adapted Fenby's biographical material about the composer and distilled it into a memorable snapshot of the creative process withstanding under highly unusual circumstances. A new audio commentary for The Debussy Film features Kevin M. Flanagan, author of Ken Russell: Re-Viewing England's Last Mannerist, making a persuasive case for it as a significant cinematic work that reinvents the biography film as a subjective, impressionistic snapshot of what made the composer significant. Much of the discussion here also concerns co-writer Melvyn Bragg, a BBC staffer who became a longtime Russell collaborator well into the early '70s. Also on the disc is a 3-minute newsreel presentation, "Land of Hope and Glory," showing Elgar conducting the London Symphony Orchestra at the opening of what is now Abbey Road studios in 1931, and a 9-minute reel of home movie footage of Elgar at home and appearing at the Three Choirs Festival in the early '30s. A

DVD of Song of Summer, a fascinating study in how he adapted Fenby's biographical material about the composer and distilled it into a memorable snapshot of the creative process withstanding under highly unusual circumstances. A new audio commentary for The Debussy Film features Kevin M. Flanagan, author of Ken Russell: Re-Viewing England's Last Mannerist, making a persuasive case for it as a significant cinematic work that reinvents the biography film as a subjective, impressionistic snapshot of what made the composer significant. Much of the discussion here also concerns co-writer Melvyn Bragg, a BBC staffer who became a longtime Russell collaborator well into the early '70s. Also on the disc is a 3-minute newsreel presentation, "Land of Hope and Glory," showing Elgar conducting the London Symphony Orchestra at the opening of what is now Abbey Road studios in 1931, and a 9-minute reel of home movie footage of Elgar at home and appearing at the Three Choirs Festival in the early '30s. A  new 10-minute HD video interview with editor Michael Bradsell focuses on his memorable experiences on Monitor with the BBC in the early '60s as Russell was trying to buck the "talking heads" format so popular at the time (and snuck plenty of crucifixes onto the screen in Elgar despite his boss's wishes), and a 30-page insert booklet features essays by Flanagan, John Hill, John C. Tibbetts, Paul Sutton, and Michael Brooke. All three titles look excellent (correctly presented at 25fps as originally shot; there's no speed up) and zoom way past the older SD masters we've had for way over a decade (not to mention the terrible, stuttery PAL conversion on the American set), getting sharper and more vivid as they go with Song of Summer looking especially deep and rich. The LPCM 2.0 mono audio sounds great for all three, and optional English subtitles are provided. Most significantly for anyone who only has the BBC American set, Song of Summer is presented in its original full-length cut with the charming intro showing Fenby at work as a silent film organist (originally for a screening of 1937's rather anachronistic Way Out West, which proved to be legally problematic here and is substituted with the more time-appropriate BFI-owned silent short, What Next?; thanks to Michael Brooke for the info).

new 10-minute HD video interview with editor Michael Bradsell focuses on his memorable experiences on Monitor with the BBC in the early '60s as Russell was trying to buck the "talking heads" format so popular at the time (and snuck plenty of crucifixes onto the screen in Elgar despite his boss's wishes), and a 30-page insert booklet features essays by Flanagan, John Hill, John C. Tibbetts, Paul Sutton, and Michael Brooke. All three titles look excellent (correctly presented at 25fps as originally shot; there's no speed up) and zoom way past the older SD masters we've had for way over a decade (not to mention the terrible, stuttery PAL conversion on the American set), getting sharper and more vivid as they go with Song of Summer looking especially deep and rich. The LPCM 2.0 mono audio sounds great for all three, and optional English subtitles are provided. Most significantly for anyone who only has the BBC American set, Song of Summer is presented in its original full-length cut with the charming intro showing Fenby at work as a silent film organist (originally for a screening of 1937's rather anachronistic Way Out West, which proved to be legally problematic here and is substituted with the more time-appropriate BFI-owned silent short, What Next?; thanks to Michael Brooke for the info).

story was made as a more traditional feature film with Vanessa Redgrave in 1968, entitled Isadora.) The American-born dancer found her calling in Europe and the Soviet Union where her private performances from the wealthy soon expanded to schooling many young girls in the creation of expressive art, coupled with a unique fashion sense inspired by her visit to Greece. Russell's film begins on a frenetic note with sped-up action including a surprising naked dance (indeed, there's more artistic nudity here than you'd ever expect in a 1966 TV production) and whirling through some highlights of her life; after that it rarely slows down as her revolutionary politics and sexual tastes are covered as she spreads her dance gospel across Europe (with some stock footage including Leni Riefenstahl clips adding to the patchwork effect). Pickles is quite an enthusiastic wonder here, and though Russell clearly has an obvious conflicted attitude about her headstrong and sometimes selfish approach to life, there's little chance you'll be bored for a minute. It's also essential for Russellphiles as he would go on to directly quote this film in his later Women in Love and The Boy Friend with amusing results.

story was made as a more traditional feature film with Vanessa Redgrave in 1968, entitled Isadora.) The American-born dancer found her calling in Europe and the Soviet Union where her private performances from the wealthy soon expanded to schooling many young girls in the creation of expressive art, coupled with a unique fashion sense inspired by her visit to Greece. Russell's film begins on a frenetic note with sped-up action including a surprising naked dance (indeed, there's more artistic nudity here than you'd ever expect in a 1966 TV production) and whirling through some highlights of her life; after that it rarely slows down as her revolutionary politics and sexual tastes are covered as she spreads her dance gospel across Europe (with some stock footage including Leni Riefenstahl clips adding to the patchwork effect). Pickles is quite an enthusiastic wonder here, and though Russell clearly has an obvious conflicted attitude about her headstrong and sometimes selfish approach to life, there's little chance you'll be bored for a minute. It's also essential for Russellphiles as he would go on to directly quote this film in his later Women in Love and The Boy Friend with amusing results.  brother of another major poet, Christina Rossetti. The focus in this Omnibus production is his relationship with model Lizzie Siddal (Paris), with whom he carries a charged but platonic relationship. An addiction to laudanum, a fling with another model, an unfortunate marriage, and a tragic fate for Lizzie (don't worry, it's given away in the chilling opening sequence) become the framework for a tumultuous collage of highlights from Rossetti's visual and written work as well as those of his peers, including a recreation of Millais' Ophelia. Though it's laced with moments of wild humor, this is

brother of another major poet, Christina Rossetti. The focus in this Omnibus production is his relationship with model Lizzie Siddal (Paris), with whom he carries a charged but platonic relationship. An addiction to laudanum, a fling with another model, an unfortunate marriage, and a tragic fate for Lizzie (don't worry, it's given away in the chilling opening sequence) become the framework for a tumultuous collage of highlights from Rossetti's visual and written work as well as those of his peers, including a recreation of Millais' Ophelia. Though it's laced with moments of wild humor, this is  probably the closest thing to a genuine horror film in the Russell canon until The Devils (not surprisingly, also starring Reed), with a dark and moody photographic style reminiscent of Hammer and Universal horror films.

probably the closest thing to a genuine horror film in the Russell canon until The Devils (not surprisingly, also starring Reed), with a dark and moody photographic style reminiscent of Hammer and Universal horror films.